A friend suggested to me that I read Freakonomics. Generally I consider pop nonfiction on economics to not be worth the time. Authors of these tomes often attribute outrageous conclusions to economic "laws." Economics has no "laws"; it only has resilent theories that can be applied successfully or unsuccessfully to individual events on a case by case basis.

I came across a copy of the book at Barnes & Nobles. The hardback was marked 30% off (a clear signal if there is one). I decided to read a few chapters to see if there was anything to it.

There is not.

The author (Steven Levitt) writes in one chapter that there was confusion surrounding falling crime rates. The answer ,he concluded, must be that as abortions rise crime must fall. His reasoning is that since low income women with no spouse have most of the abortions and since most criminals come from poverty stricken single parent homes crime falls as abortions rise.

This line of reasoning is flawed on many levels.

First, it really depends on how you define crime and what kinds of crime you are focusing on. Corporate and political malfesance has risen for instance. Second, correlation between two variables (crime and abortion) does not indicate causation. Third, where is he getting his numbers? Does anyone track the number of abortions by american citizens outside our borders? What about their income level?

Lastly, no where in his writings did he indicate the benefit or intrinsic value of human life.

Ideas are insidious. Like the flu they can be easily spread from person to person. In this case the idea is that killing is good, that it is beneficial.

Enter William "abort every black baby and the crime rate falls" Bennett. He likes the book and the ideas. His remarks were widely reported. If you missed them NPR played them for you at the top of every hour. All the major television networks, newspapers and the blogosphere were filled to the brim with his comments. He said this a few weeks after americans had watched over eight days worth of nonstop black pain, suffering, helplessness and poverty (white suffering was edited out and discredited, by no less than Tim Russert, when exposed) run rampant in New Orleans.

Further along in Freakonomics Levitt points out that terror is a powerful incentive. This is in the chapter comparing Klansmen to Real estate agents (I am not making this up). His reasoning is based on lynchings falling as Klan membership rose. By this thinking every white person should have joined the Klan in order to bring lynchings to their lowest possible number.

I do agree that terror is a powerful incentive.

Maybe Bennetts' comments were given so much press because after hurricane Katrina and Kanye West black people needed incentive to calm down. African-American fear and paranoia (for that matter all americans fear and paranoia) is well documented, and has been running high since the presidential election of 2000.

Maybe those horrific images of Katrina made a large portion of the american population wish those poor, huddled masses would just disappear.

Such specualtion is dangerous, but if you have read this far you deserve something unadultered.

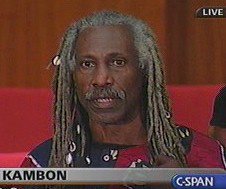

Into this echo chamber of "Freakonomics" comes Dr. Kamau Kambon who is the author of such books as "Black Guerilla Warfare: A peoples guide and manifesto" and "Subtle Suicide."

Dr. Kambon is no stranger to mainstream media. CNN's headline news featured him a few years ago saying that black people should not celebrate Christmas because it is economically and socially debilitating. This time he made genocidal comments concerning white people. Coming on the heels of the Bennett comments I am not surprised that someone voiced the obverse.

My questions are: Has Dr. Kambon read Freakonomics? Was he using terror as an incentive?

1 comment:

The best-seller Freakonomics by economist Steven Levitt and journalist Stephen Dubner never mentions the word "complexity" in its 200+ pages of entertaining correlation analysis, but at its heart it is a book about complex adaptive systems, and about the consequences of our reckless passion for treating them as merely complicated. In fact, it's more about statistics and social studies than it is about economics.

As a reminder, the difference between complicated and complex systems is that only the former are completely knowable, analyzable, and subject to rigorous cause-and-effect analysis. Complicated systems are the left-brainer's dream: To decide what to do all you need to do is identify all the variables, determine which causes which (using root cause analysis), draw systems thinking diagrams to depict the relationships, assess the possible points of intervention that could lead to a different and desired result (e.g. turn a self-reinforcing vicious circle into a virtuous one), recommend those interventions and collect your fee. Very scientific, and lots of fun. Unfortunately, in the modern world, complicated systems are fairly rare.

Complex systems are the rule, and they are not completely knowable or analyzable because the number of variables is essentially infinite, and hence the consequences of any particular intervention are largely unpredictable. You need to use a more sophisticated, less scientific approach when you're dealing with complex systems, and be more tentative in your assessments. Freakonomics deconstructs some of the many erroneous and dangerous assessments we tend to make, and actions we therefore take, when we treat complex systems as merely complicated. Its authors tell us "look beneath the surface" to discover the complexity within, and the concept is represented on the cover as an apple with the (unexpected) insides of an orange.

Dave Snowden tells us that the approach to complex systems is "probe, sense, respond" in contrast to the "sense, analyze, respond" approach appropriate for complicated systems. Analysis is futile, but that doesn't mean the probes beneath the surface can't provide us with useful and compelling information that can allow us to act in a way that will most likely be helpful and positive. Dealing with complex systems requires pattern recognition, Snowden says. Our long-term memory has a capacity of about 40,000 patterns (models, archetypes, plans, idealizations and other representations of reality), and when we see, hear or otherwise pay attention to something we only perceive and internalize the 5-10% that resonates and is consistent with those patterns, that understanding of reality. There is evidence that until someone creates a mental pattern for a phenomenon, they are unable to 'see' it at all. And once a pattern has been set in the brain, it becomes very difficult to dislodge. So when we see what looks on the surface like an apple, we can't even conceive of it being an orange inside. Freakonomics probes deeper than we normally do, challenges any assumptions about causal relationships (since those assumptions may be oversimplifying complex systems as merely complicated ones), and looks for the patterns that the rest of us can't or don't see. Some examples:

The cause of the recent drop in the US crime rate can be explained by four things, but despite scholarly works to the contrary, innovative policing practices, gun control laws, capital punishment, gun buybacks, a strong economy and an aging population aren't among them. The largest contributor to the drop in crime rate was Roe vs Wade. Read the book to find out why (and contemplate the consequences if Bush stacks the supreme court to overturn it)..

Money doesn't buy elections. While having money might secure you the nomination of a major party, once you've got the nomination the amount you spend against your opponent has no bearing on your likelihood of winning.

There is overwhelming evidence of cheating by teachers as well as students in No Child Left Behind standardized tests, and also overwhelming evidence of performance-enhancing drug use in many sports, including (although the book does not provide details) the Tour de France.

Your child is 100 times as likely to suffer harm visiting the home of a friend with a swimming pool than one with a gun in the house.

While the per-mile death rate of driving is much higher than that of flying, the per-hour rate is about the same.

Your young child is less likely to be harmed in the back seat with a seat-belt than in the front seat with a car seat; in fact, neither car seats nor cribs have any significant impact on the incidence of harm to children.

While who you are as a parent (your genes, and perhaps your passion and your example) has a significant effect on the chances your children will succeed in life, what you actually do with your children (including reading with them) does not.

Some of these findings are provocative (in fact the first and fifth have created a lasting furor). But the authors are not attempting to argue causality here, or even about the wisdom of doing certain things. They are probing, using correlation and regression techniques applied against huge amounts of data, to show what correlates with what, and in the process debunking a lot of myths about causes of and remedies for a lot of problems in our society. What they are doing is eliminating as many factors as possible, so that they can say with reasonable assurance that all other things being equal, there is a very high, significant correlation between X (e.g. availability of abortion) and Y (e.g. subsequent declines in crime rates) -- or that there is not. Draw your own conclusions.

The authors are great believers in another principle of dealing with complexity -- the importance and value of attractors and barriers (which Freakonomics calls incentives and disincentives) in bringing about desired actions or behaviour change. They believe you can learn a great deal by studying which attractors and barriers actually work in other situations (by 'work' they mean that the introduction or existence of attractors and barriers, whether natural or man-made, correlates powerfully, all other things being equal, with a subsequent desirable behaviour change. The attractors and barriers to jobs, for example, largely determine who goes into different fields, and two attractors (that it requires specialized skills you have, and that it is in high demand) and two barriers (excessive supply and unpleasant working conditions) correlate most with what the job pays. That's the reason why, the authors say, most crack dealers still live with their mothers (excessive supply of applicants for the job) and why prostitutes earn more than architects ('danger pay', higher demand and relative shortage of supply).

But they also warn against the failure to consider all of the alternative variables that might have led to that condition or behaviour. For example, children with certain names tend to end up with significantly higher education and income than others, but that doesn't mean giving your child one of these names will make their life easier. In fact, the propensity to give your child certain names correlates with a variety of other factors (such as your own education and income) which in turn correlates with your child's success. Be careful about jumping to conclusions.

There are two remarkable quotes in the book. The first is this one by economist John Kenneth Galbraith about the follow of 'conventional wisdom':

We associate truth with convenience. with what most closely accords with self-interest or personal well-being or promises best to avoid awkward effort or unwelcome dislocation of life. We also find highly acceptable what contributes most to self-esteem. Economic and social behavior are complex, and to comprehend their character is mentally tiring. Therefore we adhere, as though to a raft, to those ideas which represent our understanding.

The next quote, on the very next page, is by Paul Krugman and provides a perfect example of Galbraith's point:

The approved story line about Mr. Bush is that he's a bluff, honest, plain-spoken guy, and anecdotes that fit that story get reported. But if the conventional wisdom instead were that he's a phony, a silver-spoon baby who pretends that he's a cowboy, journalists would have plenty of material to work with.

So, say the authors, we must be wary of conventional wisdom, skeptical until and unless the data strongly supports what we are told or what we believe. Thanks to the Internet, they say, some of the 'information asymmetries' that lead to unsupportable conventional wisdom are disappearing. But what Malcolm Gladwell calls 'learned helplessness' is still with us -- our inability to go beneath the surface, challenge and debunk conventional wisdom or instinct leads us to dysfunctional beliefs and actions: That we're safer in an SUV than another vehicle, for example, or that we should spend more money and effort trying to prevent terrorism happening in our countries than we spend trying to prevent common bacterial and viral infections, for example.

And if we want to bring about real change, we need to consider what attractors and barriers we can influence that will really affect behaviour. Those attractors and barriers can be economic (e.g. a tax shift that encourages domestic employment and penalizes waste of non-renewable resources), or social (e.g. an award or promotion, or incarceration for breaking a law), or moral (e.g. an appeal to our sense of fairness, or right and wrong). The authors also recommend what they call 'bright-line' attractors and barriers (those where the attractions and constraints are very clear) over those that have consequences that are 'murkier' (less clear or less certain).

Let's suppose we want to bring about a significant drop in birth rates worldwide. First, we would need to probe to find out why they are currently as high, and as low, as they are. We could offer economic incentives to have smaller families -- though we should start by studying whether we already have them (studies suggest that, worldwide, women have on average almost one child each fewer than they would like, and cite the cost of having children as the overwhelming reason for that decision). We might offer social incentives for smaller families -- like awards or special opportunities available only to childless couples. Or we might offer moral incentives for smaller families and disincentives for large ones -- by pointing out how much large families contribute to our unsustainable way of life, or by having leaders and the media publicly repudiate the reactionary pope and other religious leaders who encourage large families, and suggest that the followers of such religions are weak and irresponsible. Levitt and Dubner would have us believe that these would be far more likely to work than political or educational methods.

But alternatively we could look at the reasons why current birth rates are where they are now, and identify incentives and disincentives that might address those reasons rather than the decision on how many children people choose to have directly. The financial pinch motivation isn't a helpful one -- there are no attractors or barriers we can use to exploit it, short of deliberately trying to plunge the world into an economic depression (and Bush and Greenspan are working hard at that). In the third world, many women claim they have large families because, in the absence of a social safety net, it's the only way they can hope to make ends meet in their senior years (and in many cases, the only way they can make ends meet period -- children are the only assets they have). Now that's something we can do something about: By providing incentives to third world countries to provide universal health care, education, old age pensions and social assistance programs for their citizens, we might dramatically reduce family sizes in the third world quite quickly. Of course, we'd need to confirm that such incentives actually work, but we could do that by studying planned and actual family sizes in countries that have significantly improved social services, controlling for other variables. And we'd need to look at the fact that, regardless of what they might say, the first and (to a lesser degree) second generations of immigrants to countries with comparatively good social services continue to have a large number of children, and understand why that is.

The point is, the means to bring about change is hiding there in the information in that orange beneath the apple peel. And while many readers have found Freakonomics either entertaining or outrageous, and are focused on the specific examples in the book, the real importance of this book is that it lends credence to complex adaptive systems approaches to understanding why things are the way they are, and how they might be made better -- through mechanisms that, when we fail to look below the surface and allow ourselves to be blinded by conventional wisdom, we might never have considered.

Post a Comment